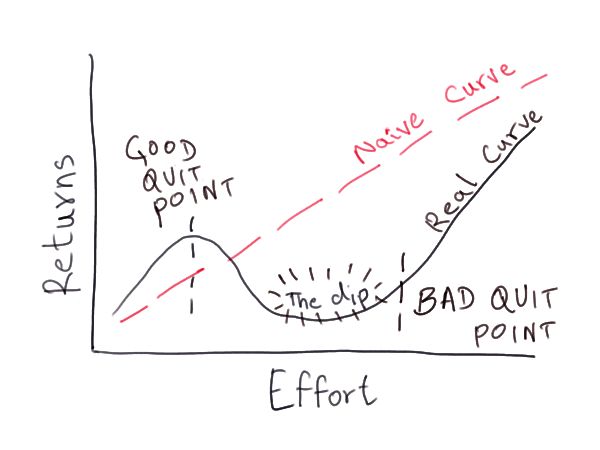

I’m usually too long-winded and often try to get a point across in extra explanatory steps, but in reading a short book The Dip by Seth Godin, I came upon a concept laid out in a page that really pertains to performance and gains. So in an effort to shorten the shit as a mentor used to say, I’ll try to improve my delivery and cut to the chase.

Stop suffering if you won’t persevere through the dip! If you want to improve, go the necessary distance.

Artwork thanks to Venkatesh Rao of Ribbonfarm blog

That’s pretty much it, but for those that need a little more here is the excerpt from the book by Godin that caught my eye. “Weight training is a fascinating science. Basically, you do a minute or two of work for no reason other than to tire out your muscle so that the last few seconds of work will cause that muscle to grow.” From the multiple perspectives of being a personal trainer, wellness coach, and now performance coach; I was like “Yeah that’s it in a sentence.” Most athletes that I see continue to work hard while not making the gains, get to that point of discomfort, and then shut it down just as the body is starting to get the message to change for the better.

Godin continued on, “Like most people, all day long, every day, you use your muscles. But they don’t grow. You don’t look like Mr. Universe because you quit using your muscles before you reach the moment where the stress causes them to start growing. It’s the natural thing to do, because an exhausted muscle feels unsafe—and it hurts.” For example, normal “activities of daily” living like walking around the house, climbing a few sets of stairs onto the deck, upstairs, or into the basement is the norm for most of us; but how about if you climb and descend a 14er. I use that example being in CO. That is just walking right?! Sure is, but it extends the number of steps and rate of ascent and descent past the body’s norm for most of us. And thus you usually are sore and fatigued from the endeavor. But when you take it to that extent, your body gets the signal to shape up for that stress in case you plan to do it again in the future. Do enough big hikes like this and it will be the new norm!

I agree with Godin’s take-home message; “People who train successfully pay their dues for the first minute or two then get all the benefits at the very end. Unsuccessful trainers pay exactly the same dues but stop a few seconds too early. ………The challenge is simple: Quitting when you hit the Dip is a bad idea. If the journey you started was worth doing, then quitting when you hit the Dip just wastes the time you’ve already invested.”

Especially that last part; it is the mindset. A lot of people say they “want” something, but their actions don’t align with their words. They are ready to endure crossing that dip of discomfort to come out on the other side stronger. And to some’s defense, it’s not their fault. They just don’t know the dip exists and they haven’t yet found the results on the other side of that zone.

That’s the joy of coaching that I love is helping people understand what’s ahead and helping them prepare sometimes more mentally than physically to handle that dip. If you lead with your mind; your body will most often follow.

All this said I’m not saying you need to push every session to failure. That is why coaching is individual and finding a path from where you are individually is important. There are times for pushing the limits, settling in well before the dip intentionally, having fun without a “training” purpose, and much in-between.

But for those sessions that you are doing to “move your dial” as I call it, here are my suggestions;

- Know and understand the goal is trying to accomplish. Is it a certain output like power or pace, desire response like heart rate, or time under tension. If you don’t understand the goal, then it’s hard to persevere the dip and why having a coach can help talk you through this.

- Define the limit or minimum effective dose (MED) to achieve the goal. Often this can be a percentage of your peak power, percent of max heart rate, repetition max, etc. An example is VO2max training. Often many people shut it down just when your body is getting any response to adapt so instead of a 1 minute VO2max, try 90sec to 4min.

- Do what you’re capable of. I often see people miss workouts or have a bad stint and immediately want to go harder to catch up. You can only do what you’re capable of and not respecting this will often result in subsequent setbacks. An example is what makes you think you can go out and do 4-minute repeats at a higher output than you’ve seen. You may get 1 and it be a PR then shot and not reach the MED for total accumulation referenced above in #2. Be realistic within reason. Maybe you set sights on 80-95% of your best 4-minute effort and go from there to rep out (see #6 below).

- Don’t hesitate to quit! Yep, that’s right, I always give the option to pull the plug, and often it’s better to and save it for another day. My protocol is after starting an activity and allowing the body to warm up, try a ramp warm-up or an initial effort, or maybe two (if short duration) before calling it. If it’s not there resort to lower intensity, recovery intensity, or rest that day.

- Getting out the door is a success. Often you’ve won if you’ve managed to make it that far. Because once you’re engaged, nearly anything done consistency is better than nothing. Unless you’re overtrained and just need rest, then that’s another story.

- Occasionally go to failure. I call it “wringing the sponge”! Even if you don’t follow a training plan, high performers I’ve seen that are all over the place have something in common. They periodically push their limits. That could be going long (and longer than their norm), going extensively hard (like repetitions of similar effort until fatigue), going intensively deep (like trying to PR or KOM their local segment), or a combination of short intensity, repeated duration efforts and volume to overload for that session.

- Know when to shut it down. This concept can be taken too far. Many of us get in the mindset of more is better, so why not push through the dip and keep going. This is a tough one to pin down but relates to #1 and #2 above. Basically, once your body gets the signal, more signal isn’t going to do any more good but induce extra fatigue and stress. And frankly, we all have plenty of that to deal with in our day to day, right? So usually setting a lower limit of the goal of when to shut it down is smart for high performers. Something like when your power drops to “X” percentage of goal, or when 2 of the 3 metrics (heart rate, power/pace, perceived effort) don’t align, then you know you’re body has gotten the message. Don’t sit there and pound sand thinking it’s going to budge.

I hope that helps and like always, I went deeper than I expected.