Structured intensity – still having fun

Are you actually hitting the training prescription (Rx)?

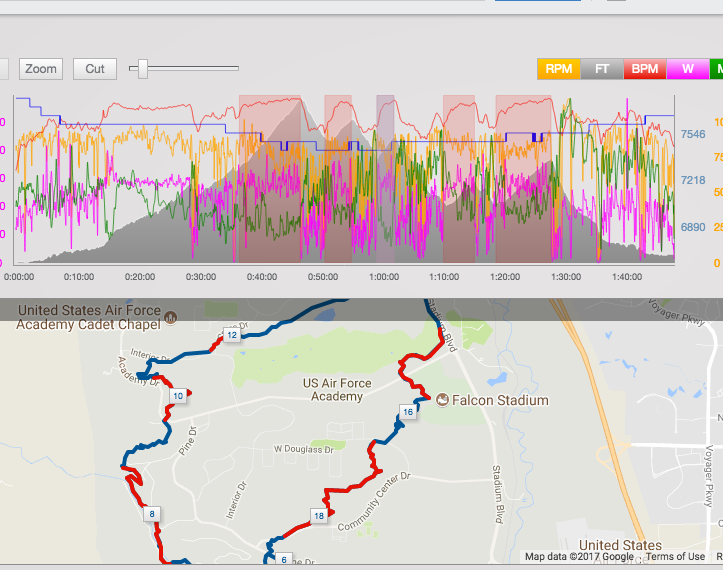

Yeah you say, I’ve got power, heart rate, etc. and doing what coach is telling me. Sure, but are you opting for a group ride on an endurance base day on your calendar or checking off a few of those Strava KOMs on an easy day when you feel good because you’ve been keeping intensity dialed down. I admit I’ve gotten probably more lax on this than I should in my day to day coaching interaction and hence why I’m revisiting it. I say that because often the act of “just do” is better for some (see my article here on that concept) than the “paralysis by analysis” that can result from overly managing Rx versus Actuals. That said there are definitely some athletes that no matter how much I pull the reins or crack the whip, the intensity just isn’t quite right. And bottom line is once you get past the “just do” then you need to be bringing intention to getting it right more times than not to see improvement.

Often the coach role is more difficult than credit is given because there is certain amount of the message lost in the translation from my intent to the actual execution. Have you ever played the game telephone with a group? Try doing that with physiology when there are varied training zones and intensities from 3 zones to 10 zones that are based on different determination methods (lab tests, long or short FTP tests, etc.). Ultimately what coaches and physiologists are attempting to do is apply simple titles to important physiological occurrences like changes in ventilatory response, lactate turn points, and metabolic changes from specific intensity efforts and durations (among other things deeper for another time and diatribe).

Sure the tools we have like Training Peaks structured workouts, devices that sync exact workouts for real-time play-by-play execution on the road, or even smart trainers controlled in ergs mode make things much easier, but that doesn’t mean that what is intended is what actually occurs. And the difficulty of building workouts based on different objectives (heart rate, power, rating of perceived exertion, pace, distance, duration, etc) starts to blur the lines of what the athlete should focus on. So yeah, you as the athlete have a very difficult task on your end as well! I try to address this as a coach that tests the workouts I build and prescribe, so I have a more intimate relationship with the execution & why it is designed the way it is. I don’t like just taking the research and applying it across the board without a little personal case study and I believe that helps weave the art into the science of coaching. Because really none of us are training in a controlled lab.

Speaking of the lab, it’s comforting, in a sense, that even when a lab study documents difficulty of subjects hitting the intended Rx in a controlled environment when we strive to hit our training Rx on a day-to-day basis with all the extraneous variables that exist in life. In an excerpt from Seiler & Tonnessen, it states “…Esteve-Lanao (personal communication) completed an interesting study on recreational runners comparing a program that was designed to reproduce the polarized training of successful endurance athletes and compare it with a program built around much more threshold training in keeping with the ACSM exercise guidelines. The intended intensity distribution for the two training groups was: Polarized 77-3-20 % and ACSM 46-35-19 % for Zones 1, 2, and 3. However, heart-rate monitoring revealed that the actual distribution was: Polarized 65-21-14 % and ACSM 31-56-13 %.

Comparing the intended and achieved distributions highlights a typical training error committed by recreational athletes.” Note the intended vs actual was off in the same direction in both groups for the respective intensities; 1) less than intended in both Low intensity Zone 1 and high intensity Zone 3, while 2) more than intended in the moderate (or threshold) Zone 2. Seiler & Tonnessen go on to elaborate, “We can call it falling into a training intensity “black hole.” It is hard to keep recreational people training 45-60 min a day 3-5 days a week from accumulating a lot of training time at their lactate threshold. Training intended to be longer and slower becomes too fast and shorter in duration, and interval training fails to reach the desired intensity. The result is that most training sessions end up being performed at the same threshold intensity. Foster et al. (2001b) also found that athletes tend to run harder on easy days and easier on hard days, compared to coaches’ training plans. Esteve Lanao did succeed in getting two groups to distribute intensity very differently. The group that trained more polarized, with more training time at lower intensity, actually improved their 10-km performance significantly more at 7 and 11 wk.”

Great you say. Maybe I’m doing it wrong. So now what? It’s not just fair to put that out there without an action item to move upon in my books. I’m here to help athletes understand themselves better whether that’s with me or others. So first off, on my end, I plan to embrace the genius in simplicity concept (as Einsten says, “ The definition of genius is taking the complex and making is simple.”) and refining my training ranges a bit for my clients while really patrolling actual versus intended.

On your end, you can do the same by going through some Q&A that will bring awareness that then allows you to set intention. Sounds so yogi-like right? Well for the better because I’m a firm believer in the concept that may stem from that line of practice.

Some things to ask; Is the hard…hard? Is the easy….easy enough? Are you blowing the Rx on less specific days and thus not hitting all the quality on the specific days? Are your performances (field tests, events, etc.) lacking the end result you believe the training input should elicit? Are you more fresh than you feel like you should be on easy/recovery days? Are your results or progression stale or plateaued? There are other questions but this is a good start that can lead you to the awareness that you are in that “black hole” It may even be slight.

A general solution to not muddle the middle. Make your good days, just that, good. And by doing that you will crave the easy days. And don’t ride upper edges of the lower zones when the Rx is recovery or endurance focused. I’m a parent now and seems like my kiddo tests my patience with this. Does “Hey that’s too close to the road” or “Shy do you have to walk on the edge of that?” sound familiar. Those parents out there know it’s frustrating and I get frustrated with the same thing from a coach perspective. I believe our society has done a great job encouraging more so when an athlete thinks, 1 1/2 hrs at 130bpm is good then I’ll do it at 150bpm. Nope not always! More is not better all the time as that may keep you from hitting the quality to really raise your ceiling in the subsequent days or you miss the intended training effect. And it’s tough to not get that hormone spike of a moderately hard ride or missing a PR on a segment, but trust me it’s worth it when your fitness improves and you start hitting those goals along with feeling better day to day versus just mediocre.

References

Foster C, Heiman KM, Esten PL, Brice G, Porcari J (2001b). Differences in perceptions of training by coaches and athletes. South African Journal of Sports Medicine 8, 3-7

Esteve-Lanao J, Foster C, Seiler S, Lucia A (2007). Impact of training intensity distribution on performance in endurance athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 21, 943-949

Esteve-Lanao J, San Juan AF, Earnest CP, Foster C, Lucia A (2005). How do endurance runners actually train? Relationship with competition performance. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 37, 496-504

Seiler S, Tønnessen E (2009). Intervals, Thresholds, and Long Slow Distance: the Role of Intensity and Duration in Endurance Training Sportscience 13, 32-53

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.